SEPTEMBER 23, 2007 – He was a modest grey-haired man sitting on the chair in a little living room in Toronto. But to be in the room with him was a privilege. Hugo Blanco, in his life and struggles, embodies the long battle of the “other America” – the America south of the Rio Grande – to emerge from generations of imperialism and oppression. Today Blanco edits Lucha Indígena (Indigenous Struggle).[1] All his life he has been an anti-imperialist and a socialist. And all his life, he has been marked by imperialism as a man who had to be stopped.

From 1958 to May 1963, he worked with peasant farmers in rural Peru, and “Blanco’s name became synonymous with anti-landlord agitation … throughout the southern sierra of Peru.” In 1963 he was captured by the police and after a trial alongside 28 of his comrades, was sentenced to 25 years in prison. “Released in the amnesty of 1970, he was exiled to Mexico the following year. Blanco returned to Peru in July 1978.” [2]

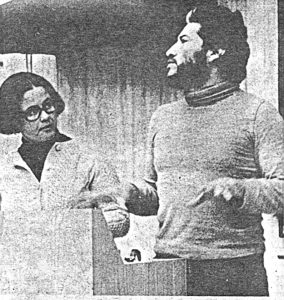

It was four years after his release from prison that I first met him, speaking at York University, part of a Canada-wide tour. The burning question of those years was coming to terms with the tragic coup in Chile.

“The Popular Unity government (of Salvador Allende) in Chile … wanted to make a revolution without the revolution. They wanted to make an omelet, without breaking the eggs.”

But that did not mean glorifying violence. “The role (of a revolutionary) is not to put bombs in some police station, but to head the organization of the masses” to help in “the independent mobilization of the masses to solve their own problems.”[3]

That was 33 years ago. The context now is both similar and different. In our day, there has also been a coup against a progressive government in Latin America – the April 2002 coup against Hugo Chavez in Venezuela. For 47 hours “we had fascism” according to Orland Chirino, a leader of Venezuela’s new independent trade unions.[4] But when one million of the poor in the barrios of Caracas rose up, Chavez was saved, and the coup was defeated. “Now we have to understand,” said Blanco “that both Venezuela and Bolivia are revolutionary governments. We have to stand by them.”

“Times are changing,” he said. There was a time when the Organization of American States (O.A.S.) was just a tool of U.S. imperialism. But this year, when Condoleeza Rice tried to have the O.A.S. condemn Chavez’ treatment of the media in Venezuela, the members refused to bow down.”[5]

Blanco argues that the fight for indigenous sovereignty has to be a central part of the fight against imperialism and for a better world, and that is now where he puts his energies. He argues that can be a key part of the fight against neoliberalism.

“Neoliberalism glorifies individualism,” he said. “But the indigenous tradition is collective, the very opposite. Neoliberalism attacks the environment. But from Chiapas to Bolivia to Ecuador to Peru, the indigenous people see their struggle and the struggle to save the environment as the same fight.”

There is a western tradition of social change. Centuries ago, one of the first documents of that tradition was Thomas More’s Utopia. But Blanco, chuckled, saying it is probably the case that More’s ideas of utopia were formed by his contact with European sailors, who had encountered the simple, collectivist life of the indigenous peoples of the American South.

There have been two tendencies of the left in the Global North. One has been to look for a pure revolutionary model and reject any struggle that doesn’t fit a pre-existing mold. The other has been to romanticize the struggles that do exist, and pretend that the masses are about to embark on the building of a socialist utopia.

Blanco’s life and work shows that the reality is much more complex. The poor and the oppressed in desperately difficult conditions are organizing to try and emerge from the horrors of imperialism. Their struggle will take complex and difficult forms, and it is the job of activists in the Global North to “amplify a much more effective solidarity” in the words of Blanco, without putting conditions on that support.

Chavez has talked about socialism for the 21st century. That is a tall order for the poorest countries of this hemisphere. But what may be possible is national liberation for the 21st century – the assertion of national independence and sovereignty, finally emerging from the domination of US, Canadian and European imperialism. We can learn much in that task from the life and work of Hugo Blanco.

© 2007 Paul Kellogg. This work is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license.

References

[1] Copies of Blanco’s newspaper can be seen at www.luchaindigena.tk

[2] Tom Brass, “Trotskyism, Hugo Blanco and the Ideology of a Peruvian Peasant Movement,” The Journal of Peasant Studies 16, no. 2 (January 1, 1989): 190n5, 179 and 192, https://doi.org/10.1080/03066158908438389.

[3] Paul Kellogg. “Hugo Blanco.” Excalibur. 1974.

[4] Orlando Chirino. “Venezuela: a society undergoing a radical transformation.” Socialist Worker 1969, Sep. 24, 2005. <http://www.socialistworker.co.uk/art.php?id=7398>

[5] Stuart Munckton. “US attack on Venezuela defeated at OAS.” Green Left. June 7, 2007. < http://www.greenleft.org.au/node/37725> Rice actually walked out of the meeting, when it became clear that the US would get backing only from Ecuador. < http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wGqGp-7WUCQ>