It was September 11, 1973, that the neo-liberal experiment began. The brutal U.S.-backed coup against Salvador Allende’s government opened the door for the “Chicago Boys” – a group of Chilean economists who had studied under Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago[1] – to “reconstruct the Chilean economy … along free-market lines, privatizing public assets, opening up natural resources to private exploitation and facilitating foreign direct investment and free trade.”[2] September 7, 2008 – thirty-five years later – that experiment came to an end, not with a whimper, but a bang. The neo-liberal regime of George Bush – more closely identified than any other world figure with the politics of keeping government out of the market – is now presiding over a state intervention into the so-called “free” market that is without parallel. When the dust settles: a) hundreds of billions of dollars will have been spent to try and fix a broken financial system; b) a generation of free-market arrogance and ideology will lie in ruins, its ideological clarion call “neo-liberalism” completely discredited; and c) the U.S. empire will be exposed as a declining (if vicious) beast. The events of September 2008 mark a watershed in the history of capitalism.

Fannie and Freddie

The first act in this story is in many ways still the most significant if not the most dramatic. September 7, 2008, the United States Treasury announced it would seize control of two institutions called Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. At the time, this represented “the world’s biggest financial bailout” (a record it would only claim for a few dozen hours). The U.S. government pledged to guarantee literally trillions in the two companies’ investments, something that estimates said would end up costing U.S. taxpayers in the order of $25 billion.

What are these peculiarly named institutions? Fannie Mae stands for “Federal National Mortgage Association” and Freddie Mac stands for “Federal Loan Mortgage Corporation.” Both are GSEs – “government-sponsored enterprises,” creations of the U.S. government, but which operate as shareholder run companies. Fannie Mae’s roots go back to the depression-era. It was created in 1938 to “provide funding to the housing market … Freddie Mac was created in 1970 to provide competition to Fannie Mae.”[3]

Their role in the housing market is indirect. Homeowners in the United States borrow money from lenders (banks and other financial institutions) just as in other countries. What Fannie and Freddy do is to buy these mortgages from the lenders. This gives the “mortgage initiators” instant cash, and a little bit of profit, allowing them to go back and quickly offer new mortgages. Fannie and Freddy then turn around and repackage the various mortgages they have purchased as “mortgage-backed securities.” They sell these securities on the secondary mortgage market – in effect borrowing money, but using these “securities” as collateral – counting on the income from the payment of mortgage principle and interest to give them cash to repay these loans.[4]

This “provides liquidity” to the housing market. It also has the effect of creating a huge incentive to get more and more people to buy houses, as at every level of this structure, incomes and profits are dependent on a constantly expanding base of home ownership. In the scheme above, there are massive fortunes to be made – by the banks and other mortgage issuers, by Fannie and Freddy and their hangers-on, and by the investors who buy up the Fannie and Freddy debt. Former Fannie CEO Daniel Mudd was in line to receive up to $8.4 million in compensation. Freddie Mac’s former CEO was in line for $15.5 million.[5] And John McCain’s campaign for the U.S. presidency, suffered a setback when it was revealed that Freddy Mac had been paying $15,000 a month from the end of 2005 until September 2008 to a firm owned by McCain’s campaign manager.[6] All had an incentive in “priming the pump” – creating incentives for working people to pony-up and enter the world of home ownership. The whole scheme works fine as long as homeowners can pay their mortgages. But if they can’t …

So base greed is an element that fed this bonfire. But that wasn’t the only, or even the biggest issue – the problems were structural. In the stock market crash at the turn of the century, huge fortunes were lost when the dot-com bubble burst. With investors burned from their experience in the stock market, U.S. interest rates were reduced to unprecedentedly low levels, as the U.S. federal reserve essentially “printed money” to stave off a deeper crisis. One key measure of interest rates, the U.S. federal funds rate, dropped below two percent in November 2001, and stayed below two percent for three years, bottoming out at just below one percent in December 2003.[7] Mortgage rates don’t track Federal Funds Rates exactly, but mortgage rates did come down, so that at their lowest point in 2003 and 2004, it was possible to get Adjustable Rate Mortgages (mortgages which increase or decrease with the rise and fall of interest rates) for between 3 and 4 percent.[8] In fact, people often were able to get mortgages below that rate – with incentives of very low interest rates in the first few years of the mortgage to encourage the plunge into home ownership. With millions moving into home ownership, the mortgage-backed securities market prospered. The effect was to create an environment where billions of dollars could flee an insecure stock market, and find a “safe haven” in the housing market, by investors moving from speculating in stocks to speculating in “mortgage-backed securities.”

This structure was riven with problems. The rush into home buying which this created, pushed house prices very high very fast. This has been a visible problem for some time. In 2006, one analyst wrote: “Cheap money turned the real estate boom into a frenzy … prices in most hot markets … soared by 55 per cent to 100 per cent (on top of inflation). Trying to keep pace, buyers increasingly resorted to riskier loans to lower monthly payments. Two types became the rage: adjustable rate mortgages and exotics.” We have already looked at the ARMs. The Exotics bear a little examination, the most extreme of which was “the negative-amortization loan, which allows borrowers to pay less than the interest due. The unpaid interest is tacked onto the principal, so the size of the loan grows every month. In 2004 and 2005, no less than 75 per cent of all mortgages were either ARMs or exotic loans, compared to 20 per cent in the late 1990s.”[9]

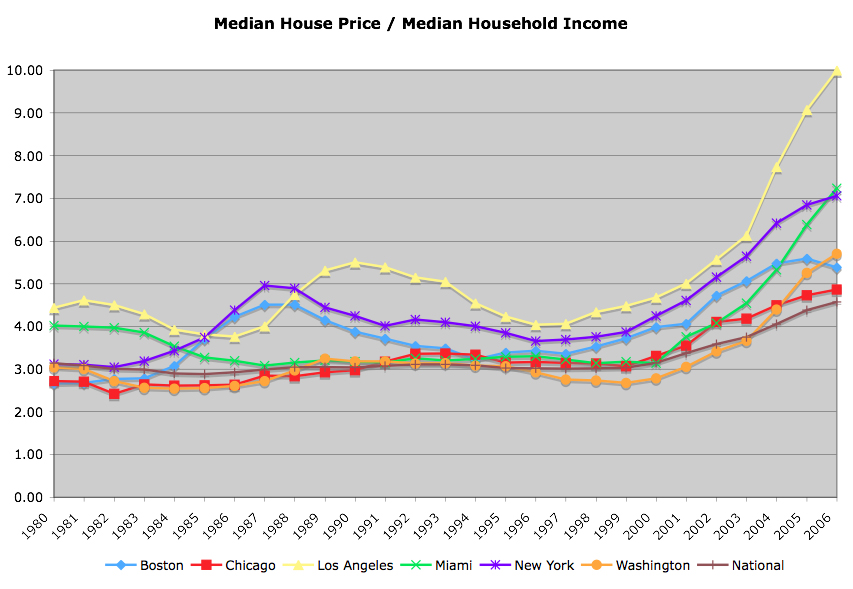

This outline is important. Some are blaming poor home buying decisions by ordinary working people for the way in which this crisis has unfolded. But it was not “reckless spending” by the poor. It was a structure, driven by greed, which created enormous pressures and incentives to abandon renting and jump into the home-buying game – simply because massive fortunes were being made. Suddenly, working people were being pressured to take on debt far in excess of their capacity to pay. The best way of measuring this is looking at the ratio of house prices to household income. The graph here shows a steady upward climb in that ratio for the United States as a whole, from the late 1990s to the mid-point of this decade – in some cities, an extremely steep rise.[10]

But interest rates don’t stay low forever. Here the story has another layer of complications. There is a close relationship in most countries between the health of the currency and the trend in interest rates. Roughly, if the country is increasing its international indebtedness, there will be downward pressure on its currency relative to other currencies. This can be countered by increasing interest rates to attract investors in spite of the increasing debt burden. At times these rates have to go up considerably to prevent a precipitous fall in the currency.

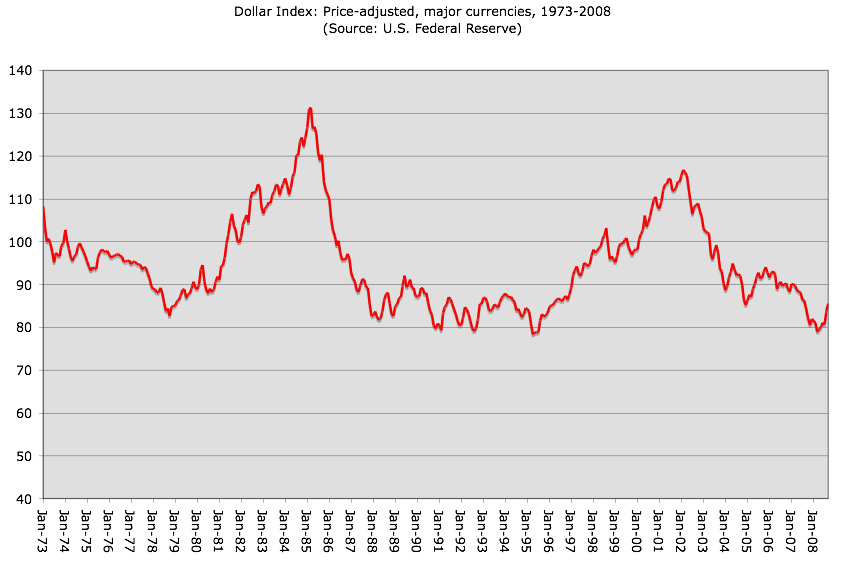

There are some who say this pressure has yet to make itself felt in the United States. The entire post-war period has been defined by the domination of the international economy by the U.S. dollar. Its “unique” place in the world economy is often seen as making it relatively immune to the downward pressure that other currencies experience when their economies become increasingly indebted. A commonly used measure of this is a comparison of the U.S. dollar to major currencies. The resulting graph does not show overwhelming U.S. dollar weakness, but rather a generations-long fluctuation with no clear trend either up or down.[11]

But there is a problem with this way of representing the health of the U.S. Dollar. The figures in this comparison go back only until 1973. This leaves out of the picture the biggest story in the history of the U.S. dollar, the effect of it “freeing itself” from the gold standard. This was the decision Richard Nixon took in 1971, allowing the U.S. to “print dollars” unencumbered by maintaining an equivalent stock in gold. The most readily accessible international comparative figures, because they begin in 1973, do not factor this epochal event into their picture. But it is possible to improvise a comparison.

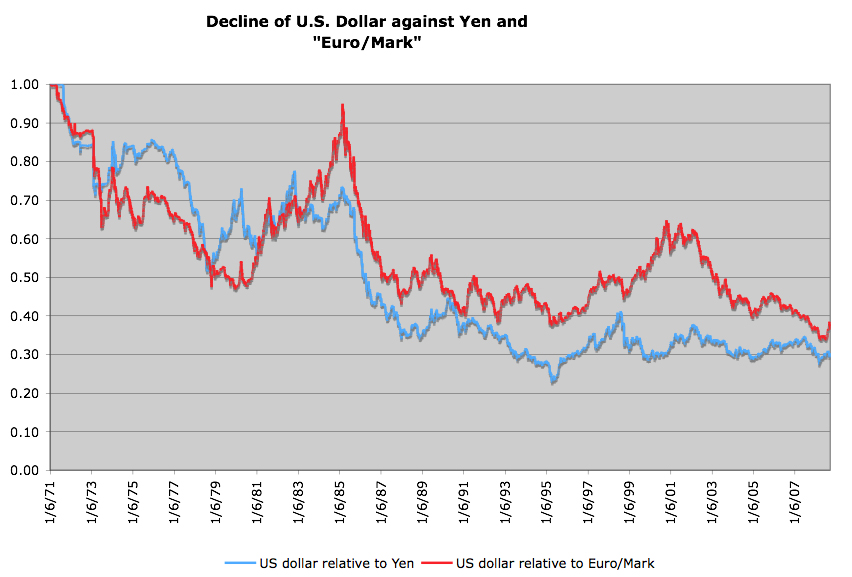

The chart “Decline of the U.S. Dollar” shows the U.S. Dollar measured against the Yen (currency of Japan) and something that is being called the “EuroMark” – a statistical composite of the Mark, formerly the currency of Germany, Europe’s biggest economy, and the Euro which has now replaced the Mark and most other major European currencies. The result is very clear. The U.S. dollar is approximately 1/3 of what it was in 1971, compared to the Yen and the “EuroMark”.[12]

The U.S. Dollar has been steadily declining against its major competitors for years. The devaluation that happened after the abandonment of the gold standard was immediate and quick, becoming precipitous in the late 1970s. This was reversed in the early 1980s by a policy of very high interest rates, then fell steadily until the 1990s, recovering somewhat in the Clinton years, but returning to decline under Bush. As the dollar declines, it inevitably leads to a day when interest rates have to go up, or the dollar’s fall could accelerate dangerously. So in Bush’s second term, interest rates have inched upwards, and this in turn became part of an environment pushing higher and higher the interest rates on millions of peoples’ mortgages.

Finally, none of this works if homeowners start to lose their jobs. When this cycle began, unemployment was at historically low levels – just 3.9 per cent, in the last four months of 2000. That increased to 6.3 percent by September 2003, dropped below five percent through the last half of 2005 and the first two months of 2008, but has since climbed steadily to 6.1 percent by August of 2008.[13]

The effects of these problems became visible in the summer of 2007. With interest rates rising, some homebuyers could not make the payments, and the number of defaults began to rise. Rising interest rates and rising unemployment, started to decrease demand for houses, so prices began to fall. And with house prices falling, many saw the value of their house fall far below the principal remaining on their mortgage – creating an incentive to simply walk away from the debt – default on the mortgage, and go back to renting. The result has been the highest rates of foreclosures in the modern era. A report from the Mortgage Bankers’ Association indicated that: ”about 2.75 percent of all home loans, or about 1.75 million mortgages, were in foreclosure at the end of June [2008], up from 2.47 percent in March. That was the highest foreclosure rate since 1979, when the Mortgage Bankers first collected the data.”[14]

As these millions of foreclosures rippled through the system, the whole flimsy structure started to shake. Between them, Fannie and Freddy had issued $3.7 trillion worth of mortgage-backed securities.[15] But suddenly, as mortgage payments started to fall because of defaults, as the assets backing these mortgages started to lose value with the falling prices of houses in the United States, these securities looked a whole lot less secure.

Bankers’ Strike

Neo-liberalism is a modern restatement of an old “free-market” orthodoxy. Markets know best. Let the “hidden hand” of the market do its magic, and a million individual decisions based on individual self-interest, will end up with a virtuous direction for the economy and society as a whole. Sometimes there are barriers to the operation of this hidden hand – too much government intervention, too much regulation being two of the most often cited. Get rid of them. The state’s role is to do away with regulation, to unfetter the markets from the hands of government, to let the markets do their work.

So – from the standpoint of neo-liberal orthodoxy, it is a matter of some indifference that Fannie and Freddy were under stress. Joseph Schumpeter argued last century that capitalism worked through processes of “creative destruction” where periodically whole sections of capital are destroyed in economic slump. This process, while painful, was central to the working of capitalism, clearing the ground for a new round of investment, the way in which a forest fire burns away the underbrush, allowing new saplings to reach for the sky. In Schumpeter’s words the “creative destruction” of competition, bankruptcy and consolidation “revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism. It is what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist has got to live with.”[16]

But the capitalists who made the decisions leading to the impasse of the U.S. financial system are not going to live with the consequence of their actions. Something pushed the neo-liberals into acting against neo-liberal orthodoxy and save those capitalists from the consequences of their actions. What the neo-liberals discovered was that the U.S. economy was not all-powerful, that had they let the process go too far, and the consequences of a full-blown cycle of “creative destruction” would have been disastrous. The issue was not simply one of mortgages – it was about the structural problems of the international, not just the U.S., capitalist system.

So far only one part of the story has been told, the story of mortgages, Fannie and Freddy, and their selling of “mortgage-backed securities”. The next question that has to be asked is, who buys these securities? The economists’ answer is that they are bought by “risk-averse investors such as banks, pension funds and central banks around the world,”[17] investors in other words who want a guaranteed return on their investments, and little or no risk of these investments turning into worthless paper. Fannie and Freddy’s total liabilities is mostly debt, most of it from the sale of mortgage-backed securities, and it totals in excess of $1.7 trillion dollars.[18] Significantly, increasing portions of that debt have been sold to non-U.S. banks and investors. The top five in reverse order, as of June 2007 were Taiwan ($55 billion), South Korea ($63 billion), Russia ($75 billion), Japan ($228 billion) and China ($376 billion).[19] The entire structure then was increasingly dependent on the willingness of banks and other institutions in these countries, to continue giving Fanny and Freddy billions of dollars.

This summer, it came to an end. Under pressure from their eroding mortgage business, Fannie stocks fell from $67.30 a share October 5 2007, to just $7 a share, September 4, 2008.[20] Freddy stocks followed the same downward slide, from $63.43 to $4.95.[21] Suddenly, non-U.S. investors, particularly in Asia, began to worry. The slide in share value of Fannie and Freddy raised the possibility that the two companies could go bankrupt. That would leave banks and investors in Asia and elsewhere holding pieces of paper worth billions of dollars less than their face value. “Chinese banks ‘were probably facing significant losses,’ says Logan Wright, an analyst with Stone & McCarthy Research.”[22]

Bankers from outside the United States began to apply leverage. In the first half of 2007, central bank holdings of Fannie and Freddie securities increased on average by $22 billion a month. But in 2008, those holdings fell by $27 billion from mid-July through early September.[23] And the Financial Times reported in August under the headline “Bank of China flees Fannie-Freddie,” that “Bank of China has cut its portfolio of securities issued or guaranteed by troubled US mortgage financiers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac by a quarter since the end of June. The sale by China’s fourth largest commercial bank, which reduced its holdings of so-called agency debt by $4.6bn, is a sign of nervousness among foreign buyers of Fannie and Freddie’s bonds and guaranteed securities.”[24] “The threat of a central bank buyers’ strike was real,” accord to Brad Setser, a former Treasury Dept. official and now a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.[25]

Neo-liberal orthodoxy dictated “let the market rule,” let the processes of creative destruction work themselves out. But bankers outside the U.S. who stood to lose billions from this market failure said; “Creative Destruction be damned. If you don’t act, we will start withdrawing our money. We are already doing it. We will not let you ‘cleanse’ your economy by leaving us holding worthless pieces of paper.” So facing an enormous catastrophe, Bush and the U.S. administration suddenly switched from the world’s biggest neo-liberals, to the world’s biggest state-capitalists, when they intervened to guarantee the debt held by Fannie and Freddy. Many of their neo-liberal ideologues were left wondering what had hit them. This whole thing might, said one commentator become a “nightmare scenario, the descent into quasi-socialism” which “balloons the national debt and wrecks foreign investors’ faith in the economy.”[26]

The state and capital

But of course this has nothing to do with “socialism” – unless it is a kind of Frankenstein’s Monster socialism, where the state robs from the poor to give to the rich – because that is exactly what is happening: tax dollars from U.S. workers to be used to pour into the balance sheet of two failed corporations. It is a myth of the neo-liberals that the state is separate from the market. There is of course the central role of state militarism. The British Navy ruled the waves so that British business could penetrate every corner of the globe in the 19th century. The U.S. military has time and again overthrown governments in Latin America to keep the hemisphere open for business. But there are also the directly economic ways in which the state is intimately tied to the development of capitalism. British imperialism jealously protected its industries behind the walls of empire. India did not build its rail network with British steel and rolling stock because of the market, but because of imperialism.[27] Japanese capitalism burst into the 20th century after the Meiji Restoration used the Japanese state to mobilize resources in order to industrialize.[28] Canadian capitalism had at its core the construction of a continental rail network, which bankrupted the private capitalists, and was only finished because of the state-capitalist “National Policy.”[29] In South Korea, the industrial revolution in the post-war era was inconceivable without the “chaebols”, very much creatures of the South Korean state.

The myth that capitalism is about the retreat of the state, and that socialism is about its reverse – state intervention – is a myth made easier by the long nightmare of Stalinism, where there were states which called themselves “socialist” and which said the same thing as the neo-liberals only in reverse: “We are socialist because the state owns everything: never mind the absence of civil rights and the absence of democracy.” But the Stalinist states are long gone, and a new generation is returning to the roots of the socialist movement, understanding that socialism is about popular control, workers’ control of the economy and the state, or it is about nothing. It can be important to have the state intervene to fix problems in the economy. But the key question becomes – who controls that state? In the United States, we can be pretty sure that the state is controlled by the corporate elite.

That capitalist state, having got the taste of government intervention to save capitalism from itself, has now become ravenous for more. Fannie and Freddy were only two of the institutions under stress because of economic problems in the United States. September 16, the U.S. Federal Reserve took over American Insurance Group for $85 billion. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi criticized the rescue, calling the $85 billion a “staggering sum.” Ms. Pelosi said the bailout was “just too enormous for the American people to guarantee.”[30] But that staggering sum has now been dwarfed by another even larger sum. United States’ Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson is asking Congress to come up with $700-billion to clean “toxic assets” out of the U.S. financial system. What he wants is to have enough money on hand so that any bank or financial institution which has a piece of paper that is looking pretty worthless, Paulson will have the money to say “no problem, we’ll take it off your hands.”

How do you come up with this “worst-case scenario” figure? Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke said in testimony that “ ‘various metrics’ could be used to arrive at that $700 billion number. It is 5% of $14 trillion in outstanding mortgage debt and roughly the same percentage of the $10 trillion to $12 trillion of commercial bank assets. ‘So it seems like an appropriate amount relative to the size of the problem.’”[31]

Seems like an appropriate amount. You would have thought he would have hired someone to get figures so that he could be a little more definitive given the “size of the problem.” What we are looking at is a trillion-dollar intervention by the U.S. government into the financial system of the world’s biggest economy – the biggest ever economic intervention by a state into any economy anywhere – that is going to change the shape of economics and politics for a generation. The crisis brings into focus three central points.

1) The decline of the U.S. and the Danger of Militarism

There has been a sharp divide in anti-capitalist circles over the position of the U.S. in the world system. Theorists like Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt argued that empire had become disembodied from the state.

In contrast to imperialism, Empire establishes no territorial centre of power and does not rely on fixed boundaries or barriers. It is a decentred and deterritorialized apparatus of rule that progressively incorporates the entire global realm within its open, expanding powers. Empire manages hybrid identities, flexible hierarchies, and plural exchanges through modulating networks of command. The distinct national colours of the imperialist map of the world have merged and blended in the imperial global rainbow.[32]

The actions of states in the context of the current crisis shows this analysis to be inadequate. The states of the various central banks which had holdings of U.S. securities, including the state in China – all have particular interests that they seek to assert. Similarly, the state in the U.S. is suddenly enormously and obviously important to Empire – doing what no corporation on its own can do, mobilizing the tax resources of working people to bail out the financial system. “Empire” is just as bound up with the state system – a system of competing and predatory states – as were all previous systems of imperialism.

Theorists like Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin have challenged Hardt and Negri on exactly this point, seeing very clearly the continuing role of the state in shaping the field of power that has been called “Empire.” However, in the place of a system of imperialist states, they tend to reduce “Empire” to just one state – the overwhelmingly dominant U.S. state. They have argued that U.S. penetration of European and Asian capital is so profound as to make irrelevant and archaic any notion of inter-imperial rivalry.[33] But this view too is being revealed as problematic. The long decline of the U.S. dollar, documented above, is an indication of the worsening competitive position of the United States against its rivals in Europe and Asia. And the way in which this bailout took shape – in part from the threat of a strike by central bankers outside the United States, refusing to further invest in U.S. securities, is another powerful indicator of a changing world order. The U.S. remains the world’s biggest economy and most powerful state. But its position relative to others has been in decline for decades, and this débacle shows that the decline is ongoing.

There is a very developed literature, under the heading of the “Permanent Arms Economy,” that makes a compelling case to explain this decline.[34] The long-term structural shift of resources into arms has effectively starved key sections of the U.S. economy of investment, allowing others in the world system to catch-up and in some cases economically overtake the United States. The massive military presence sustained by the U.S. since the Korean War, has been accomplished at the cost of its international competitiveness. Other countries have invested in their “civilian economies” to a much greater extent than the U.S., overtime weakening the relative position of the U.S. in the world system, something now being starkly revealed in the current economic crisis.

But we also know from the last empire to fall under the weight of its arms spending – the Soviet Union – that an addiction to war might have negative effects for an economy, but it is still an addiction. The Soviet Union stayed mired in pointless and bloody wars abroad virtually until it collapsed in the years 1989-1991. The U.S. addiction to arms spending is likely to have the same contours – bad for the economy, but unshakeable for the state. It means that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are likely to be with us for some time.

2) Ideological crisis of neo-liberalism

This September financial shock, has opened up a period of deep confusion and splits for the hegemonic ideology of neo-liberalism. The $700-billion bailout is being pushed by Republican George W. Bush, the world’s pre-eminent neo-liberal. Its principal opposition has come from – the staunchly neo-liberal Congressional Caucus of his own party.[35] It was these neo-liberal hardliners who were at the core of the defeat of the $700-billion bailout package in the first vote in Congress.[36] The neo-liberal monolith has cracked over its key precept – that markets should be “free” of the state.

Without any question, this chaotic, sudden shift from the neo-liberal orthodoxy of the small state and the free market to a new state-capitalist interventionism – this shift will like a thunderbolt make millions question the orthodoxies of neo-liberalism. Why are the bankers being given billions, while those who have lost their homes get nothing? In the parlance of the journalists, “why is Wall Street getting billions that come from the pockets of the ordinary folk of Main Street”? If we are going to have state intervention, why not go all the way – use the money for public transit, green jobs, public housing, schools and education, investments that help ordinary people not overpaid bankers?

But as Naomi Klein has pointed out, a crisis in the ideology of neo-liberalism is not the same thing as a retreat from the policies of neo-liberalism – the privatization and deregulation which have so plagued working peoples’ lives for more than a generation.

It would be a grave mistake to underestimate the right’s ability to use this crisis – created by deregulation and privatization – to demand more of the same. … the dumping of private debt into the public coffers is only stage one of the current shock. The second comes when the debt crisis currently being created by this bailout becomes the excuse to privatize social security, lower corporate taxes and cut spending on the poor. A President McCain would embrace these policies willingly. A President Obama would come under huge pressure from the think tanks and the corporate media to abandon his campaign promises and embrace austerity and “free-market stimulus.”[37]

It is worth remembering that one of the modern architects of neo-liberalism, Margaret Thatcher, was very clear on this point. Thatcher is associated with the phrase “there is no alternative” or “TINA” – usually seen as justifying the unbridled rule of competition. Susan George writes that Thatcher:

… was well known for justifying her programme with the single word TINA, short for There Is No Alternative. The central value of Thatcher’s doctrine and of neo-liberalism itself is the notion of competition – competition between nations, regions, firms and of course between individuals. Competition is central because it separates the sheep from the goats, the men from the boys, the fit from the unfit. It is supposed to allocate all resources, whether physical, natural, human or financial with the greatest possible efficiency.[38]

But in Thatcher’s classic and most often cited use of the term, this was not quite what she said and this was not quite her point. At a speech to the Conservative Women’s Conference, May 21, 1980, Thatcher’s theme was the way in which wages were increasing too quickly.

Wages in the public sector are still higher than the country can afford … earnings will have to rise much more slowly if we are to avoid still more unemployment and if we are to get inflation down. It is too often forgotten that during the last two years there has been considerable increase in average living standards. What we produce has been growing much more slowly. We have to get our production and our earnings into balance. There’s no easy popularity in what we are proposing but it is fundamentally sound. Yet I believe people accept there’s no real alternative.[39]

The point is, Thatcher was not in the first instance driven by an abstract commitment to the market, but by a class commitment to transferring wealth from workers to employers. In this, the role of the state is a tactic, not a principle. The Thatcherite state showed its capacity to intervene against workers’ wages with real brutality during the bitter miners’ strike of 1984-1985.[40] Neo-liberal orthodoxy may lie exposed as nonsensical, but the class which brought us neo-liberalism remains in power, motivated by the same project – capturing the wealth produced by “Main Street” and making sure it ends up in the pockets of “Wall Street.”

3) The need for social movements against capitalism in all its forms

Which leads to the most important point, the need to insist that Thatcher and the neo-liberals are wrong – there is an alternative. In the 1990s and early 21st century, there was a magnificent international movement against neo-liberal globalization. The great protests against NAFTA led by the Zapatistas, the protests against the WTO in Seattle, against the FTAA in Quebec City, against the G8 in Genoa – these protests mobilized hundreds of thousands.

But the political leadership of these movements rested in groups like ATTAC in France or the Workers’ Party of Brazil. For them the target was not capitalism itself, but capitalism in its neo-liberal form. Neo-liberalism is now in open crisis, but the alternative on offer is not re-assuring – a strong state that protects corporations from their own excesses, and does so by taxing and squeezing the wages of ordinary workers. The problem is not just neo-liberalism. The problem is capitalism, whether in its “neo-liberal” or “state-interventionist” form. The next round of anti-corporate mobilizations needs that understanding at its centre.

We are seeing today in North America the hollowness of the neo-liberal dystopia. Others saw it earlier. It was after all the indigenous people of Chiapas who rose up against the neo-liberal North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in January, 1994, the peasants of Cochabamba in 2000 who stopped the water privatizers in their tracks, the masses of Caracas who in 2002 prevented the coup d’état which would have restored neo-liberalism in Venezuela, part of the swelling rage of all the oppressed in Latin America who, the principal road-block to the 2005 imposition of the U.S. led neo-liberal Free Trade Area of the America (FTAA). Perhaps just as neo-liberalism’s birth was in Latin America, it will similarly be Latin America where we will see the beginnings of the new social movements challenging capitalism in all its forms.

© 2008 Paul Kellogg. This work is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license.

References

[1] Gilberto Villarroel, “La herencia de los ‘Chicago boys’,” BBCMUNDO.com, December 10, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk

[2] David Harvey, Spaces of Global Capital: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development (New York: Verso, 2006), p. 12

[3] “US rescues giant mortgage lenders,” BBC News, September 7, 2008

[4] Alana Semuels, “Q&A about mortgage giants Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac,” Los Angeles Times, September 8, 2008, www.latimes.com

[5] The Associated Press, “Answers to your Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac takeover questions,” New York Daily News, September 11, 2008, www.nydailynews.com

[6] Jackie Calmes, David D. Kirkpatrick, “McCain Aide’s Firm Was Paid by Freddie Mac,” The New York Times, September 23, 2008

[7] Bank of Canada, “Monthly Series: V122150: Federal Funds Rate”, www.bankofcanada.ca

[8] HSH Associates Financial Publishers, “HSH’s National Monthly Mortgage Statistics,” www.hsh.com

[9] Shawn Tully, “Real Estate Survival Guide,” Fortune, Vol. 153 Issue 9, May 11, 2006, pp. 94-102

[10] Calculated from Joint Centre for Housing Studies, The State of the Nation’s Housing 2007, “Additional Table: Metropolitan Area House Price-Income Ratio, 1980-2006,” www.jchs.harvard.edu. Figures are not yet readily available for 2007 and 2008. However, an update has been released to one analyst, which shows the same general trend, with the addition that from 2007 on, house prices have started to fall – the graphical representation of the bursting of the housing bubble. See CalculatedRisk, “Update: Ratio Median House Price to Median Income (2008 Report),” June 24, 2008, http://calculatedrisk.blogspot.com

[11] U.S. Federal Reserve Board, Federal Reserve Statistical Release, H.10 “Foreign Exchange Rates,” “Price-adjusted Major Currencies Dollar Index,” www.federalreserve.gov

[12] Derived from “FXHistory®: historical currency exchange rates,” accessed September 24, 2008.

[13] Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey,” http://data.bls.gov

[14] Vikas Bajaj, “Foreclosures Rose as Delinquencies Eased in Quarter,” The New York Times, September 5, 2008

[15] According to Peter Coy, “Back on Track – Or Off The Rails?” Businessweek, September 22, 2008, p. 24

[16] Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (New York: Routledge, 1994), p. 83

[17] Coy, “Back on Track,” p. 24

[18] MarketWatch, The Wall Street Journal Digital Network, www.marketwatch.com and Forbes.com

[19] U.S. Treasury Dept., as reported by Bruce Einhorn and Theo Francis, “Asia Breathes a Sigh of Relief,” Businessweek, September 22, 2008, p. 32.

[20] Yahoo Finance, http://yahoo.finance.com

[21] Yahoo Finance, http://yahoo.finance.com

[22] Einhorn and Francis, “Asia Breathes A Sigh of Relief,” p. 32

[23] Einhorn and Francis, “Asia Breathes A Sigh of Relief,” p. 32

[24] Saskia Scholtes and James Politi, “Bank of China flees Fannie-Freddie,” Financial Times, August 28, 2008

[25] Einhorn and Francis, “Asia Breathes A Sigh of Relief,” p. 32

[26] Coy, “Back on Track – Or Off the Rails,” p. 25

[27] Clarence Baldwin Davis, Kenneth E. Wilburn, Ronadl Edward Robinson, Railway Imperialism (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1991)

[28] Colin Barker, “Origins and Significance of the Meiji Restoration,” 1982, www.marxists.de

[29] Stanley Ryerson, Unequal Union (New York: International Publishers, 1968)

[30] Edmund L. Andrews, “Fed’s $85 Billion Loan Rescues Insurer,” The New York Times, September 16, 2008

[31] Joshua Zumbrun and Liz Moyer, “Your Guide To The Bailout Debate,” September 24, 2008, Forbes.com

[32] Michael Hardt, Antonio Negri, Empire (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2000), pp. xii-xiii

[33] See essays in Leo Panitch and Colin Leys, eds., Socialist Register 2004: The New Imperial Challenge and Socialist Register 2005: The Empire Reloaded (London: Merlin Press). For an exchange that goes over this controversy in detail, see: Alex Callinicos, “Imperialism and Global Political Economy,” International Socialism 108 (Autumn 2005); Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin, “ ‘Imperialism and Global Political Economy’ – A Reply to Alex Callinicos,” International Socialism 109 (Winter 2006); and Alex Callinicos, “Making sense of imperialism: a reply to Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin,” International Socialism 110 (Spring 2007) – all available online at www.isj.org.uk.

[34] See Michael Kidron, Capitalism and Theory (London: Pluto Press, 1974) for a classic development of this thesis. Some of Kidron’s writings are available at The Marxists Internet Archive, www.marxists.org

[35] Sheldon Alberts and Don MacDonald, “Bailout plan stalls as conservative Republicans voice their opposition,” The Vancouver Sun, September 26, 2008

[36] Carl Hulse and David M. Herszenhorn, “Lawmakers Defy Bush and Party Leaders, Rejecting Bailout,” The New York Times, September 29, 2008

[37] Naomi Klein, “Now is the Time to Resist Wall Street’s Shock Doctrine,” The Huffington Post, September 25, 2008

[38] Susan George, “A Short History of Neoliberalism: Twenty Years of Elite Economics and Emerging Opportunities for Structural Change,” Transnational Institute,, March 24, 1999, www.tni.org

[39] Margaret Thatcher, “Speech to Conservative Women’s Conference,” Margaret Thatcher Foundation, May 21, 1980, www.margaretthathcer.org

[40] See, among other accounts, Alex Callinicos and Mike Simons, The Great Strike: The Miners’ Strike of 1984-5 And Its Lessons (London: Socialist Worker, 1985)